Day of the Dead

Mano a Mano: Mexican Culture Without Borders has celebrated the Day of the Dead since 2004. It was one of the first organizations to educate about the cultural importance of this tradition in New York. Our mission is to preserve and present Mexican culture, including its rich traditions and contemporary relevance. Our first celebration occurred in 2004 at Madison Square Park in Manhattan; since 2005, it has been held at St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery. During October and early November, our organization visits schools to teach about the holiday and collaborates with several organizations and cultural institutions to create ofrendas and conduct workshops.

Ofrenda 2021 Picture by Mari Uchida

Day of the Dead Ofrenda (altar) Picture by Alejandra Regalado

Ofrenda Altar honoring Maria Felix

Ofrenda 2021 Picture by Mari Uchida

Our past Day of the Dead celebrations.

About the Day of the Dead

DAY OF THE DEAD (Día de Muertos) has been an important celebration in Mexico since pre-Hispanic times. The Mexica [meˈxika] (Aztecs) memorialized their dead for two months in the summer: Miccailhuitontli (for children) and Hueymicailhuitl (for adults). Spaniards introduced the Catholic calendar and moved the practice of honoring the dead to All Souls Day, celebrated on November 2nd.

The tradition is rooted in the native Mexican belief that life on earth is a preparation for the next world and that it is important to maintain a strong relationship with the dead. Families gather in the cemetery during this celebration to welcome the souls on their annual visit. In the houses, people prepare altars known as ofrendas with traditional ephemeral elements for the season, such as cempasúchil (marigold) flowers, copal incense, fresh pan de muerto bread, candles, papel picado, and Calaveras (sugar skulls). Photographs, mementos, and favorite items used by the departed are included.

The Mexica believed that when a person died, their teyolia, or inner force, went to one of several afterworlds, depending on how they died, their social position, and their profession (not by their conduct in life). There were special afterworlds for children, warriors, women in labor, and those who died by drowning. This tradition continues today with special altars built on specific days to honor different groups: October 28 for those who died in accidental or violent deaths, October 29 for individuals who drowned, October 30 for forgotten and lonely souls, October 31 for unborn children, November 1 for deceased children, and November 2 for adults who died a natural death, as well as for all other deceased adults. The order of those remembered may vary depending on the region or tradition. The Mexican diaspora has taken this tradition to celebrate it across borders. Mano a Mano: Mexican Culture Without Borders continues this tradition by highlighting important contemporary themes, public figures, and community members.

Here are some frequently asked questions.

Is the name of the holiday Día de los Muertos or Día de Muertos?

In Mexico, the celebration is traditionally called Día de Muertos. However, in the U.S. and other English-speaking countries, it is often referred to as Día de los Muertos, a back-translation of the Day of the Dead into Spanish. Our organization proudly maintains the traditional name Día de Muertos, which reflects our commitment to honoring and preserving our authentic cultural heritage.

When is the Day of the Dead celebrated?

In Mexico, people prepare for the Day of the Dead well in advance. Farmers sow flowers, and artisans craft decorations, sugar skulls, folk art, and other items for the festivities. The Day of the Dead is celebrated in Mexico from October 28 to November 2. In many rural areas, the celebrations begin on October 28. However, in larger cities and metropolitan regions, festivities mainly occur on November 1 and 2.

Do people dress up or wear face skull makeup for the Day of the Dead?

During the traditional observance of Día de Muertos, it is not customary to wear costumes or makeup. Instead, it is a time for families and communities to honor and celebrate their loved ones. While dressing up and wearing skull or Catrina makeup has become popular, these practices are not traditional or centuries old. The style and designs we see today have evolved in the last decade, influenced by the media, films, art, and cultural factors.

What are alebrijes, and what is their connection to the Day of the Dead?

Alebrijes are brightly colored Mexican folk art sculptures of fantastical creatures often made from papier-mâché (cartonería) or carved from wood. The tradition of alebrijes originated in Mexico City and was created by artist Pedro Linares in the 1930s. In the Pixar film "Coco," the creators depicted Alebrijes as spirit animals and linked them to the Day of the Dead; however, Alebrijes are not spirit animals and have no connection or association with the holiday outside the movie's narrative.

Is the Day of the Dead celebrated with parades?

It's important to note that parades are not traditionally associated with the Day of the Dead. In fact, they were only invented as a concept by Hollywood producers. Until recently, parades were a rare occurrence. However, in 2016, a Day of the Dead parade was held in Mexico City, inspired by the James Bond movie Spectre, and the extras who participated in the film made it an annual event. Since then, the parade has gained popularity, and many people have started organizing their parades, taking inspiration from the Mexico City event. It's crucial to note that parades can give first-time observers a false impression of how the Day of the Dead is celebrated.

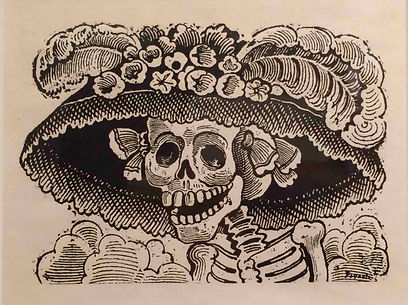

La Calavera Catrina - created by printmaker José Guadalupe Posada around 1910. Photo of the print taken in 2013 at the Mexican Museum of San Francisco by staff of Mano a Mano: Mexican Culture Without Borders.

Section of Diego Rivera's 1947 fresco, "Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park." The four figures in the center are, from right to left, the printmaker José Guadalupe Posada, La Catrina (the Skeleton), the painter Frida Kahlo (behind La Catrina), and Diego Rivera as a young man (in front of Kahlo). Museo Mural Diego Rivera, originally, Hotel del Prado, Mexico City; photo: Garrett Ziegler, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Who is La Catrina, and what does she represent in celebrating the Day of the Dead?

Named initially La Calavera Garbancera, later renamed La Catrina, is a female skeleton with a fancy hat. The Catrina was first created in 1910-1912 by artist José Guadalupe Posada as a satire of native women adapting European dress during his era. Diego Rivera included "La Catrina" in his 1947 painting "Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park," making her a national icon. The Catrina represents the idea that death is inevitable and equalizes everyone, regardless of their social status or wealth. In the last several decades, it has been associated with and has become a symbol of the Day of the Dead or Día de Muertos.

It is worth noting that while her imagery has been incorporated into the Day of the Dead celebrations, her presence is minimal or absent in traditional rural celebrations.

La Catrina is now common during the Day of the Dead celebrations in large cities, often appearing in costumes, makeup, and artwork. However, it wasn't always linked to the holiday. This association has become more prevalent recently, particularly with the emergence of social media.

How do we differentiate the Day of the Dead from Halloween?

The Day of the Dead and Halloween are two distinct and unrelated holidays. The Day of the Dead originated in pre-Hispanic times in central Mexico. It is celebrated to honor and welcome the departed. On the other hand, Halloween has its roots in the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain in Northern Europe. It is celebrated on October 31, the eve of All Saints' Day. During Samhain, people dressed in costumes and lit bonfires to protect themselves from evil spirits.

The holidays present a contrast; whereas the Day of the Dead is a time to honor and welcome the spirits of the deceased, Halloween is traditionally intended to fend them off.